Tuesday, May 30, 2006

A Journey called TRIPS Compliance

Monday, May 29, 2006

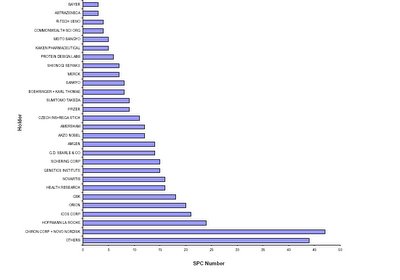

Medicinal Product SPCs Holders (1991 - 2003)

The figure above represents the number of SPCs sorted by holders.

Source: European Generics Medicines Associations

The figure above represents the number of SPCs sorted by holders.

Source: European Generics Medicines Associations

1991 - 2003 Medicinal Product SPCs

Thursday, May 25, 2006

What is Indian Pharma’s Next Move?

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

Viread: The Next ‘Pre-grant Opposition’ Target

Tenofovir which was disclosed in U.S. Patent No. 4,808,716 exhibits ionic nature at physiological pH and low cellular permeability and thereby demonstrated low oral bioavailability during preclinical trials. After more than 10 years of discovering Tenofovir, Gilead Sciences revealed a lipophilic oral prodrug of tenofovir --- Tenofovir Disoproxil, a bis (isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl) ester of Tenofovir --- having better oral bioavailability as compared to Tenofovir. TDF when orally administered metabolized by diester hydrolysis to tenofovir in the systemic circulation, which is subsequently metabolized by phosphorylation to form pharmacologically active metabolite tenofovir diphosphate responsible for antiretroviral activity. Pre-1995 compound Gilead Sciences disclosed Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate in U.S. Provisional Application Serial No. 60/022,708 filed July 26, 1996 against which U.S. Patent Nos. 5,922,695 (genus patent) and 5,977,089 (species patent) were issued on July 13, 1999 and November 02, 1999 respectively. Even though TDF is a new form of a known compound, Tenofovir, it was disclosed after 1995 and thereby making Viread eligible for patent protection in India. Now, the critical question is whether Viread has sufficient merit to overcome the barrier of section 3 (d). The Word is ‘Efficacy’ According to section 3 (d), the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance will not be considered as a patentable invention. Further, in the explanation part it is specifically mentioned that salts, esters, ethers, polymorphs, metabolites, pure form, particle size, isomers, mixtures of isomers, complexes, combinations and other derivatives of known substance will be considered to be same substance, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy. Considering section 3 (d) along with its explanation, it is clear that a new form of a known compound with improved efficacy would be enough to overcome barrier of section 3(d) and thereby sufficient to stand the requirement of inventive-step under section 2 (1) (ja). As it is technically clear that TDF has significantly better oral bioavailability as compared to earlier known tenofovir, the likelihood of Viread to overcome the ‘efficacy’ barrier of section 3(d) is apparent. Generics 'Dilemma' Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate tablet was given marketing approval in India on August 17, 2005. So, the next critical question would be whether generic companies infringes Gilead’s patent if granted by the Patent Office. Answer is Yes! According to section 11A of the Patents Act, 1970 all patent applications will be publish after completion of 18 months, after which application will be open for pre-grant opposition. Further section 11A (7) states that an applicant, on and from the date of publication of the application for patent and until the date of grant of a patent in respect of such application, will have the like privileges and rights as if a patent for the invention had been granted on the date of publication of the application with a proviso that the applicant will not be entitled to institute any proceedings for infringement until the patent has been granted with a further proviso thatthe rights of a patentee in respect of applications made under section 5 (2) before the 1st day of January, 2005 shall accrue from the date of grant of the patent with yet another proviso that after a patent is granted in respect of applications made under 5 (2), the patent-holder will only be entitled to receive reasonable royalty from such enterprises which have made significant investment and were producing and marketing the concerned product prior to the 1.1.2005 and which continue to manufacture the product covered by the patent on the date of grant of the patent and no infringement proceedings will be instituted against such enterprises. Proviso of section 11A (7) of the Patents Act, 1970 clearly states that a patent-holder cannot a bring an infringement suit against generic manufactures which have made significant investment and were producing and marketing the concerned product prior to the 1.1.2005 and will continue to manufacture the product covered by the patent on the date of grant of the patent by paying reasonable royalty to the patentee. Proviso clearly emphasizes that generics should be producing and marketing the patented product prior to 1.1.2005 which is, in fact, not the case with Viread. Generic companies got marketing approval form the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) on August 17, 2005 and started marketing their generic versions after 1.1.2005. Under newly amended patent act, it is apparent that in case of patent issuance against the pending patent application for Viread, Gilead is not bond by the proviso of section 11A and can institute patent infringement lawsuit against generic manufactures, if they continue to market their generic versions after patent is granted. Irrational Apprehension Opposing Viread patent application on the grounds of apprehension that it would make antiretroviral drug dearer is completely irrational. Presently, a strip of 30 tablets of generic Viread costs around Rs. 4000 in India which itself is expensive for Indian public. Even if patent is granted and Gilead launches Viread at higher cost then Government can curtail its price under Drug Prices Control Order, 1995 which can further be monitored and revised time to time by National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority. Government also have the option to invoke compulsory license is case of adverse situations. But presently, it seems to be that only generics want to have the whole cake.

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Patent holder deserves the Monopolistic Rights

BECAUSE, THERE IS A CAUSE……

Monday, May 15, 2006

Patent Insurance: Teflon Coating on Armour?

- Defence expenses, including legal attorney fee, declaratory statements, injunctions and appeals.

- Damages covered, including judgments and settlements; previous lost royalties and previous profits, interest and costs; attorney fees assessed by the court.

- The policy covers directors, officers, employees, company, its subsidiaries, all products, and all patents – utility, process, and design.

- Coverage of new acquisitions, previous acts, arbitration, and dispute resolution procedure.

ENFORCEMENT INSURANCE Some companies do not apply for patents because of the misconception that there is huge cost and time involved in obtaining and protecting the patents. On the contrary, the cost of applying and securing a patent is only a fraction of the cost of developing the new product. If the invention has financial viability, then it makes good sense to apply for a patent. And once the patent is granted, insuring the patent would be the next logical step as it reduces the financial burden of fighting any legal suits. An insured patent also discourages probable infringement, as the infringing firms would fear the financial strength of the patent holder (due to the muscle power of the insurance company) in fighting any legal battle. INSURANCE PREMIUMS Premiums for patent insurance depend on the patent and/or the product being protected. They usually range between 2-5% of the insured amount. Damages of up to $1 billion are covered under the insurance, while $20-30 million are common. Insurance limits up to $15 million coverage per patent are available. Deductibles start around $50,000-$100,000 and include a co-insurance percentage after the deductible. The co-payment can vary from 15% to 25%. Defense expenses such as legal fees, declaratory statements, injunctions, and appeals are usually covered by the policies. The insurance coverage premiums for a $1 million patent starts at $25,000. The factors that determine the premium rates are the past records of the firm, the care taken in patent research to prevent infringement and the firm’s own research and development work. However, before providing the insurance coverage, insurance companies carefully consider the following aspects of the insured company:

- Past attempts at handling and enforcing patents

- Licensing programmes

- Detailed patent claims of the insured’s patented product

- Steps taken by the company to protect and monitor conflicting patents

- Existing and potential competitors in related markets

- Sales and market share of top five companies in the market

- The known patents and patent-holders in a particular field

- The availability of capital resources for marketing a competitive/patented product.

WHO SHOULD OBTAIN PATENT INSURANCE? Every company which manufactures or markets new products must cover its risk by obtaining patent insurance. The key words here are “new products.” If new technology, new design or new functionalities are available or embedded in the products that are manufactured or marketed by a company, it is recommended that the company must obtain patent insurance. Also, several aspects of a business have inherent intellectual property material which may not even be known to the business. For instance, a business may have websites that need to be protected. Websites are publications, and as a publisher, the company may be liable to infringement claims. If the new technology is patented by the company, they will benefit from the patent pursuance insurance or enforcement insurance. If the patents are not held by the company, it is possible that some other company holds the patents, and therefore the company must have the patent litigation insurance, to mitigate the risk of possible infringement suits against the company. Patent insurance of both kinds (defense and offence) should be obtained by companies of all sizes – small, medium and large. Because, patents are size-neutral, and so is its insurance. In fact, the smaller companies must try to get more patents and more Enforcement Insurance to benefit from licensing to bigger companies. The bigger companies, on the other hand, must obtain Liability Insurance to protect against lawsuits brought against them by smaller companies. Of course, the bigger companies must also strive to have their own patents and the Enforcement Insurance on those patents. In short, if you have your own patents, you must have Patent Enforcement Insurance. If you don’t have patents on your product line, you must have Patent Liability Insurance. In addition to everything stated above, every company must perform infringement analysis to ensure that their products do not infringe on anyone’s patents. On the other hand, they must also establish market vigilance procedures to ensure that their competitors are not infringing on their patents. EVERYBODY HATES INSURANCE! A patent is the armour on the products. A patent insurance is the Teflon coating on the armour, which ensures that no infringement will stick. Having said that, it is also fair to mention that patent insurance is not the main highlight of a business plan. Of course, there is always the option to “do nothing.” It is the first course of (in)action; it is the path of least resistance; it is a procrastinator’s quick decision, and it is a no-premium but high-risk option. Yes, it is a simple decision to be without insurance. However, the people who do not obtain insurance, knowingly or unknowingly, still have, what is termed as ‘self-insurance.’ They are just not paying premiums. In a self-insurance scenario, you don’t pay premiums, but you might, one day, pay a heavy price.

And, if and when, that day comes, and an infringement occurs, against your patents, or against your products, and if it finds you without a Patent Liability Insurance or Patent Enforcement Insurance, and then, and there, you find the competitor to be aggressive and fierce, and you feel a sense of loss; and, for that day and hour, if you want to save this article, to be read and reviewed – yes, by all means, save it now; and, on that day, read it again; and then, surely you will read it in a different light.

Today’s post comes from M. Qaiser and P. Mohan Chandran with iPrex Solutions, Hyderabad, India. This article was earlier published with globally leading US-based online portal --- IP Frontline. Copyright © 2005, iPrex Solutions.Thursday, May 11, 2006

Patent Applications filed in India